I don’t know how to start this shit, yo…

While this particular review has nothing to do with Nas, that famous line from Illmatic might be the best way for me to actually start this piece. For one, Common has been one of my favorite artists for a long time now; at one point he was indisputably my favorite rapper, so I have to shy away from the possibility of bias. For two, there was a lot of things to quote, both within the album and outside of it, but very little of it stands out enough to warrant that kind of quotation.

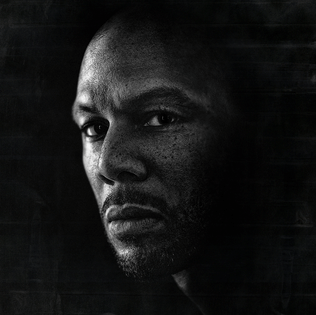

Common has always been a thinking man’s rapper. Even in his debut Can I Borrow a Dollar? when he was still Common Sense, there was a depth to him masked behind his youth and cocky, sexually-tinged demeanor. Resurrection upped the ante with his now signature introspection, and outside of a few slip-ups (Electric Circus as an experiment, Universal Mind Control as diarrhea) he’s maintained this subtle blend of old school battle rap, thought provoking content, spirituality and social commentary. So when Nobody’s Smiling was announced, an album with a base in the violence that has seemed to plague Chicago for years now, I have to admit that I was on the fence.

I didn’t think about it as a concept album, not really. A concept album follows a theme and the various tracks maintain that theme in some kind of format. Lupe Fiasco’s The Cool was hardly a concept album, but it did follow that formula. Nobody’s Smiling is more systemic commentary of various topics that might be associated with or even act as a panacea to the gunplay that plagues the major city. While not a problem in any capacity, Nobody’s Smiling lacks the oomph of some of Common’s other albums, which follow grand, overarching themes of love by and large. Tackling the issue of violence in Chicago is admirable, but it doesn’t necessarily paint Lonnie Lynn, Jr. at his best.

Common is at his best when he’s in storyteller mode, and as a friend of mine once said, not too many rappers can craft a story over a few tracks. No Fear has him harkening back to tracks such as Faithful and U, Black Maybe, with the first verse painting a picture of a young hood with no fear and no regard for his life or any other, which is similar to the character of Michael Young History of Lupe Fiasco fame. And after that, the commentary is almost exclusively through the eyes of Common and the hodgepodge of younger upstarts that join him, with the exception of Sean Anderson, who still hasn’t done anything to make me respect him as a musician. While this is Common’s album, the finest qualities of it aren’t necessarily him but his guests and the production.

First, the guests. Elijah Blake, Snoh Aalegra, Dreezy, Lil Herb, Vince Staples and the flawless Jhene Aiko, they bolster the album through their fresh faces and fresher voices, whether lending a hook or a verse, and maybe it is the passion they can show because of their lack of relative fame or their excitement in being on a major project, but while they may not all express the same level of lyricism that Common does or even sound as polished, they more than make up for it their enthusiasm and believability. Dreezy in particular delivers a verse on Hustle Harder that admittedly isn’t amazing in content but it is breathtaking in sheer presence and force. If the heart and soul of any album are the voices and the backdrops they have to accompany them, it isn’t Common so much as these guest vocalists, minus Big Sean, that pump blood throughout.

With that in mind, the production is handled exclusively by No I.D., longtime collaborator with Common, executive vice president of A&R for Def Jam and creator of Cocaine 80s, a group that is featured on this album. No I.D. produced albums are nothing new for the man referred to as Chi-Town’s Nas, as Resurrection and The Dreamer/The Believer were both exclusively produced by the Chicago-based producer, and Can I Borrow a Dollar? and One Day It’ll All Make Sense were mostly produced by him. There’s always been a soulful quality to No I.D.’s production, mixed with a grittiness that benefits specific artists it seems. To be fair, the rappers get the gritty; R&B singers get something a little more classy.

That’s all to say that No I.D., as per usual, succeeds in delivering head-nodding quality with every track. Opening track The Neighborhood is every bit as stirring as anything Kanye West himself produced on Be, whereas songs like Real and the title track incorporate some minor clever samples and minor electronic influences, respectively, to deliver something that encourages repeat listens. No I.D. might just be at his best on the track Kingdom, providing a beat that invokes the spirit of the black church, high praise, stark revenge and questionable salvation with a snare that stands out even with all those elements.

Nobody’s Smiling doesn’t have a problem so much as an unfortunate quality of following a legacy of at least three classic albums. Common isn’t at his best or worst on this LP, and while many lines and verses are quality they don’t stand out as much as something from his earlier works or even Finding Forever. This is his (technically) second attempt at a concept album, the first (technically) being Universal Mind Control, and the greatest issue with the album isn’t Common as a performer but Common’s focus. What promoted as a look and examination into Chicago’s issue of violence comes across as a personal and somewhat impersonal point of view that doesn’t share the bleakness of some of his featured guests. It isn’t unwelcome, but secondary.

Common himself is in quality form lyrically, but he goes between general bravado and real concern for Chicago, but it’s hard to understand his focus as he never stays on anything for too, too long. Outside of the occasional zinger (“My whole life I had to worry about eating/I ain’t have to time to think about what I believe in” (which coincidentally plays into his forte as a storyteller)) he isn’t on anything that really pushes the bounds of what he’s capable of.

The brightest spot of the album comes with the final album track, Rewind That, which has Common waxing poetic over his fallen friend and beat maker extraordinaire J. Dilla. Between Common simply baring his soul and No I.D. masterfully gives us something the blends his personal brilliance with the brilliance of the late Jay Dee, it’s touching because it sounds like it doesn’t quite belong. With all the commentary from the rest of the album, Rewind That stands with heart-tugging final tracks from other hip-hop albums devoted to J. Dilla such as The Roots’ Can’t Stop This and the Common-assisted Music for Life off of DJ Hi-Tek’s second album. I don’t know if that’s ironic or intentional, but I’d replay Rewind That all day, or even put it in a playlist with the aforementioned songs and let it repeat.

A lot of people say this is Common’s best album since Be. I’m not inclined to argue with them either, I just don’t agree. For me, this is a solid Common record, but the folly is the focus, and rather than being a shining example of Common’s legendary stature in the rap world, it’s more of a B+ effort than his A and A+ quality work. So it joins Finding Forever as something that was fun to listen to and quite good, but not quite great. And maybe it’s my bias towards Common, but great is my personal standard for him.